I’m standing at his hospital bedside in a black suit and in my hand is his pallid-grey fist. Shallow breaths as the ventilator shifts, the gentle rise and fall of the bed sheets across my father’s chest. Beneath my NHS-issued face mask, there’s a comical look on my face, like someone whose insides have been kicked out. I remind myself this is not a memory I wish to keep, but I will keep it all the same.

Before it happens, I would have believed losing my father would be unbearable, but in reality and amid the clatter of day to day life, the event is not what the anxious mind fantasised. I am lost amongst the mundane rituals of being. We live and we die, such is life. I am a god amongst the godless, privy to machinations beyond this life. I stop at the checkout, smile at the cashier but you are dead.

My oldest friend leaves me without need of any words. I have said everything I would want to say. Yet in time, many thoughts will settle and swirl, drawing patterns in the sand. I recall our conversation a week before, the words he says. “Don’t worry about me. I’m fine. I’ll see you soon.” Perhaps he was at least half right.

My father is a kind man. He’s trained as an engineer, in love with vintage cars and motorcycles. He dismantles anything that breaks, whether it gets put back together or not. Sometimes he’s angry, not at us but at the world around him, things he breaks and then later tries to fix. Life is hard on him. He calls me ‘Bugsy’ after Ben Siegel. I won’t know who that is until I’m much older.

He tells me once that he felt nothing in his life had ever worked out the way he had hoped. This brings me pain.

I awake one morning after a dream. In it I’m still a boy and my father comes to me holding a small animal in his hands, it’s a squirrel, wounded and dying. He talks to me about losing his own father, tells me the body is a machine, and that one day it simply ceases to function.

My mother and I dig small hole in the grave of my grandparents. My father’s ashes are dense like sand and the colour of oatmeal. It bothers me to think of the bones of his fingers, ground down to dirt. We bury him there, covered with a marble plaque I order off the internet. If I was alone, there would be no words but my mother says a few. If there had been money enough, I would forgo this experience altogether. I am not a gravedigger nor do I ever wish to be one.

I am young, sat on our garage floor, upset at the sight of dead rabbits, lined up on the concrete. The sun is low, creeping through the trees as I run my fingers through their soft fur – the flesh beneath is hard as clay. I am an only child, living in the countryside. I am lonely and these animals are my companions. My father digs a hole in the garden and sits with me. He tells me the rabbits are gone, that their bodies were just a shell, no longer the creature I cared for. He says it’s okay to be sad, but nothing can hurt them anymore.

I’m thirty-six. I curl up on the floor of my bedroom with my knees against my chest. I press my forehead against the carpet and the tears are soft and warm against my skin.

In another time, my father is in overalls. Beams and bricks stack against the back of our family home. My father and the man he once apprenticed to, Charlie, are building an extension – a small conservatory which extends out from the kitchen. I find a photograph of this amongst old receipts and junkmail. This is the thing that will destroy us. My father is young then. He builds his home, works to make a family. Charlie is a kind man and his death will one day break my father’s heart. Beneath his shed, my father tells me, his widowed wife will find hundreds of empty whiskey bottles – posted through the floorboards after he said he would stop drinking.

I am about eleven when we lose our family home. It’s a large Victorian house bought by my grandfather. My gran tells me they had paid a few thousand pounds for it at the time. There will be a day when this seems implausible. A barometer hangs in the hallway with my grandfather’s name on it. I will never meet him.

I climb out of upper-story windows, parkour before parkour. I can get from the top floor window to the back garden in seconds, this is how I will evade capture. My father tells me not to walk on the conservatory roof, but he doesn’t mind as long as I’m careful. He shows me how to build a wall in the garden with bricks and cement. My neighbour tells me the names of all the flowers.

Bailiffs are a familiar sight at our door, along with teachers and education officers. I am in love with my childhood, with this home. I am young and I am good. Sometimes though the teachers physically drag me to school, I kick and scream but my feet don’t touch the floor. In my mind I mirror my family’s battle with bailiffs. My father has many books. I am Joeseph K, I am beneath the wheel. Why doesn’t anyone help me?

My father is drunk, but he is not a drinker. We are coming back from a friend’s party when we find a hedgehog. He wraps it up in his coat and lets me pet it before letting it go. He tells me he doesn’t mind that I don’t go to school, he thinks it shows character.

My grandmother takes out a loan, one with an interest rate so high that even Sisyphus would laugh. She takes it out to build our conservatory and tells no one. One day the figure owed will be unrecognisable. My father will argue it isn’t legal, that there were no witnesses. No one will care though. It will cost us many things – a house, a home, a family, a childhood, a marriage.

The rain is at my window and each bead of liquid is gold and bauble-like. Everything smells of cigarettes. It haunts me. His house is in ruins and I am the one that has ruined it. I hunt for bills and old photographs, try and make sense of the mountains of stuff. At night his empty room, clings to my subconscious. He is not there.

I am sent to boarding school and the house is sold, swallowed by solicitors and landlords. I’m sent to psychiatrists, to official buildings where my future is dissected. The education officer’s name is Colin. He argues for home education, but all we hear talk of is duty. He wants to help but I’m blacklisted for truancy. He quits his job. I wish I knew his last name.

Everything happens so quickly, we are leaving the house I grew up in. There is a hole in the plasterboard, covered by the headboard of my parent’s bed. Something about it sticks – revealed by turmoil, the fist-sized crevice, pale and crumbling. This house, my home – the soft evening light crawling across the wall of these empty the rooms. I stare at. Everything is unspoken in this moment. My father sits me in the van beside him, I look at the goldfish swimming in a bowl at my feet.

I have no friends. They have all left. I have no GCSEs, I have no means of getting them. I am wild and strange, I have not been a part of the world and it is one that terrifies me. I sit with my father in cafes filled with other strangers, many who will sit all day nursing cups of tea. This seems the last stop before the streets, a place for those with no home to go to. At night I cannot sleep, my heart aches with loneliness. I walk the town until the sun breaks the clouds, I long for a human voice. I haunt the house where I grew up, walk past it, wondering if some part of us remains inside. I drift through the city centre, the lights from the shop windows make you feel as though life could come. I hope never to be this alone again.

We live in the country until the money runs out, we don’t have hot water or electricity. We sell what we have to make enough money for food. I sleep with a towel balled against my stomach to stop it aching. We toast bread on an open fire, when that is gone, we even boil grass.

The car runs out of petrol. My father slams his fist into the dashboard over and over until his hand is bleeding. He bows his head against the wheel and tells me my mother has left him. He cries but I don’t know what to say. I am thirteen. We will never speak of it again.

I’m holding my father’s ashes in my hands and don’t want to be. They feel heavy – the weight reminds me of a newborn baby. I walk down the steps and follow my mother to the car. The berries on the tree are impossibly red.

Rain falls on a small trailer filled with boxes. The rent is overdue. We are being evicted. I’ll struggle to remember any of this when I’m older, it’s being shut out. My mother comes to help us move, but I’m not going with my father. He’ll one day say he ‘lost me too’. I hope he didn’t feel that way at the end.

I meet my dad each day in a Spudulike on Sidwell Street. He saves up for weeks to buy me a Christmas present. It costs fourteen pounds. It never seems to stop raining and the air is cold. His hair is turning white.

Even now I dream of the rain slick streets, my father at my side – it is always night. I fear these other people, in nightmares they are killing eachother, a mob of anger that my father somehow guides me through.

My mother is crying. She hugs me as we look down at the plaque we’ve put on my father’s grave. I don’t want to come here again. Perhaps I won’t.

My gran says ‘drechtly’. She cooks fried breakfasts in lard, leaving cigarette ash in the egg yolks. My mother paints flowers and my father makes model airplanes. He sits me on his knee and shows me how to hold a paint brush. When it is done, he puts the model I made on the shelf with all the others.

My gran is eighty years old and will be homeless in two months, that’s what the letter says. ‘Voluntarily homeless’ for not claiming benefits they didn’t know they were entitled to. She’s living with my father in a B&B whilst their case is assessed, The Osprey in Exeter, where they share a tiny single room. The place is filthy and filled with rats. The room above holds a family of four with two children. A young mother in the building complains of rats getting into her baby’s cot. It is 2001, not 1890. I’m sixteen years old. If I could find the people that did this – the loan sharks, the solicitors, the council workers – I would kill them all.

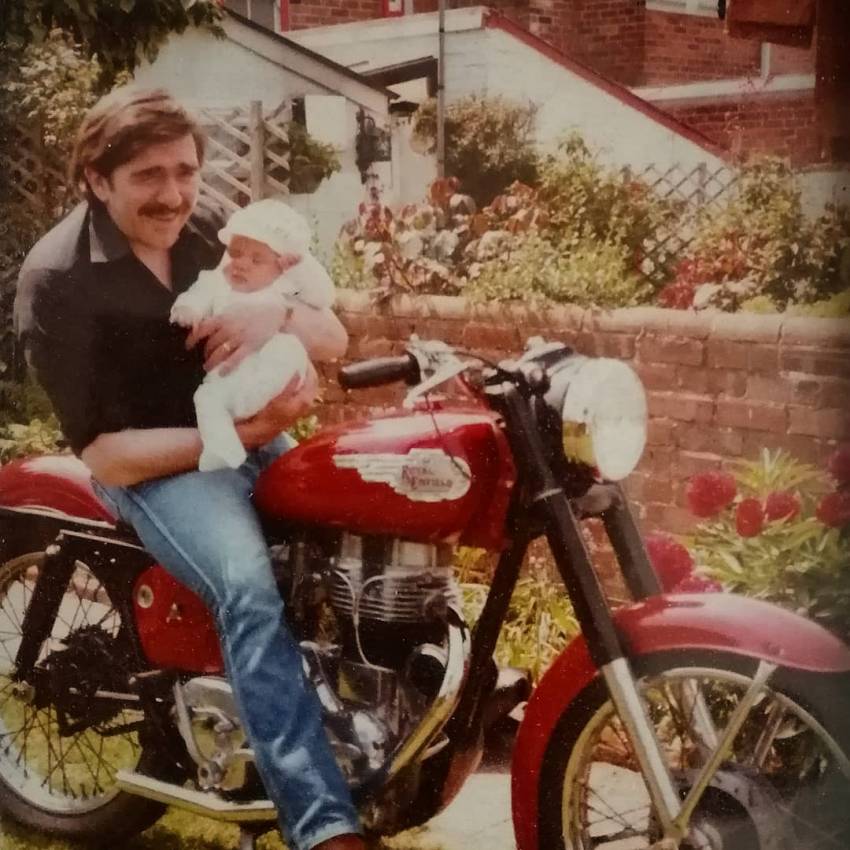

My mother puts his picture in a frame. It appears on my shelf two days after he’s gone. In it he cradles a baby in his arms, his legs slung across a Red Royal Enfield. That baby is me and the smile he has is real.

I run from school and in a panic my father grabs me by the wrist, leaving a red mark. He begs me to forgive him for hurting me. I don’t go to school that day.

I am rarely spoken to as a child. I am told about the civil rights movement, about Kafka and Herman Hesse. I listen to cassette tapes as I fall asleep – Leonard Cohen, Simon and Garfunkel. The lyrics paint deep images in my mind, shaping my dreams. I am free and I am wild. School is childish and dull, my world is full of artists and philosophers.

Two men are at my father’s door, they tell him they’ve been sent to get the money he owes for rent overdue. They’ve been hired by his old landlord. They try to force their way in, one of them tries to punch my father and his ring cuts my father’s forehead. My father hits him back, splitting the stranger’s lip. They run away.

My father goes to the police, but nothing happens. He phones his old landlord, tells him he knows what he did and that hiring thugs to collect debts without a licence is illegal. No one ever comes for the money again.

They drag me. The psychiatrist has examined my case, but this is what he has come up with. Why must I always be dragged or carried by strangers? My father disapproves, he thinks it will do more harm than good. I am ten. I have learnt to run and hide. To run from adults is nightmarish, they will always catch you. You have to be able to climb, you have to slip through holes in fences, not be afraid of brambles cutting into your skin. The psychiatrist makes my father come with him and he is silent as I kick and scream. Everyone sees, all my friends. I’m having a panic attack. They sit me in a side room as I gulp for breath. They make two of my closest friends sit with me. What the hell is happening?

My father tells me he regrets letting them do that. He says it has haunted him for years.

I’m in a car with an education officer, a different one. He shows me a piece of paper, a document he says he can sign at any time. With his signature they will put my parents in prison and I’ll be sent to a foster home. I will dream of that, of my parents being taken away. I hate him with a passion. When I’m older, I will wonder if the letter was ever even real. One day, when we’re driving, he will talk to me about my rabbits. He keeps them too – the Orange Rex, a breed I’ve only ever read about. I feel disappointed somehow. I can’t hate him so easily.

My father sits in the library each day. He reads the law books, he writes down notes. He writes to Exeter council, he tells them he’s writing to the papers – a story about making an eighty year-old woman homeless a month before Christmas, it mentions all their names. He gets offered housing benefit.

My gran dies – I see her a week before. She complains her rings won’t fit on her fingers and says she can hear music playing from upstairs all day long. I can’t hear it. We’d go out on day trips but she’s gotten too frail now. She can still read the papers without glasses though and tells me stories about the people she once knew. I say, “I’ll see you soon.” “I hope so.” She replies. She’s ninety-two and dies in the night whilst reaching to pull on her slipper. It’s a good death.

“That’s the end of that,” my father says, though not unkindly. I will think of this when he dies.

My father is older now, he’s remarried and has a dog. His council house is flooded with raw sewage, no one comes to clear it up. He suggests it’s a metaphor for how our government treats people in this country.

He tells me nothing in his life ever worked out the way he’d wanted but he also tells me that he still believes tomorrow might be different, that at any moment he could decide to do something and just do it.

I can’t look at him when he’s smoking. His forefingers are tarred and dark as earth. He coughs and I anticipate his death. My father has withdrawn from life. I don’t realise it at the time but as I trawl through his house, uncovering photos of better times, I realise how much has changed. The bailiffs, the barristers, the education officers and solicitors. They take their toll. Exeter City Council with their endless threats, the unpaid water bills and the countless court summons. He only wants to be left alone.

I am the only witness left to these events. We will never speak of them. Is that what really happened? I’m certain it was, but how can I ever know. There is no one to tell me otherwise. Not anymore.

Before it happens, I believe losing my father will be unbearable, but nothing is unbearable. We either survive it or we don’t. The doctor asks me what he would want – his body is beyond repair, deep in a coma – cigarettes and coffee, microwaved food and poor living. Defeated in spirit, my oldest friend was once angry at government. Angry at Brexit, at the hedge-funders, the Tax Dodgers – the Tim Martin’s of Wetherspoons, the Richard Branson’s and the Alan Sugar’s. He was angry at Exeter City Council, at the back-handed housing contracts, the brown envelopes from building firms, at the spikes to stop rough sleeping. I’m at an event and councillor Peter Edwards talks about supporting theatre, I cannot applaud – I know his expense account, watch him drinking the complimentary ale and remember the rat infested guesthouse, his campaigns against the homeless.

I use a shovel to clear the last of my father’s possessions. They’ve rotted into compost; I don’t know what they ever were. The walls are stained black with mould and the skirting boards are buckled with damp.

The doctor asks me what my father would want and I tell him not to keep him alive for us. He says my father has had the maximum amount of treatment and that we’re not doing him any service. I agree it’s time to let him go. I’m not with him when it happens, I can’t watch him die. He’s so deeply sedated, he doesn’t feel a thing. I think of the end of Ride The High Country, the dying gunfighter. “I don’t want them to see this, I’ll go it alone.” My father loved that film.

The doctor asked me what my father would want but I’ll tell you what I didn’t tell him. My father wanted to live in a world where people didn’t take the jobs that bring such misery. Where people weren’t kicked from homes, or lived in fear of debt collectors or bailiffs. He wanted to live in a world where security and well-being weren’t traded for profit, where housing and utilities were human rights not business ventures. He wanted to live in a world where the rich howled in agony each time they paid taxes, where people didn’t have to queue for food banks or sleep in shop doorways. A place where those that take to stormy seas in tiny rubber boats can eventually find dry land.

Here’s what my father would say, “Cool Hand Luke the parking metres, raise pitchforks to the Tim Martin’s and take a torch to the second homes. There are people in power who would strangle you in your sleep just to turn a profit. There are those that beg for light, teeth kicked-out, bones broken and they crawl in the dirt beneath the trampling feet of those that buy and sell what you deserve to have. Make them feel shame for it. Make them suffer, make them foot the bill. Damned be those that kick down.”

I hang my grandfather’s barometer on the wall, my childhood seems so close I can almost touch it.

My father is dead. I look at the ocean, the sun is out and the heat shimmers, welding the sky and sea together without seam. My father is dead. There are children playing in the tide as seagulls wheel through the azure blue. My father is dead.

A flower now is no less beautiful than it was in a world where he was alive, the sun is no colder and the air is no less sweet. I am grateful for his death, grateful for the conversations, for the friendships. I am grateful he did not suffer at the end, I am grateful he didn’t know we would not talk again. Life is perfect, all is well. I fix the thought inside my head.

I leave the hospital and I know I won’t speak with him again. He dies and I am certain he no longer exists. I feel no ghostly presence, no sense of being watched. I feel awake. Everything is so real and so crisp. A smile hangs on my lips, soft and child-like.

A leaf arches its back against the sun, a flower grows. A blade of grass stands tall, before receding back into the earth. We are told life is a story, that we are a hero in our own adventure. We speak about purpose and success, but in doing so, we create failure. We make a plan and we set goals, but a river is a river and a tree is a tree – they don’t aspire to be those things, they simply are. I realise I have no need to fulfil some illusion of narrative, I don’t need to be a musician or an artist, I don’t need to fulfil some quota to prove I am more than I am. I don’t fail by not doing those things, because I’ve already succeeded. We live and we die and that is fine. A crooked tree is no less a tree than one that grows straight. My mind is empty and in that emptiness is the entire universe.

Is this the last thing you teach me?

My father mixes the cement, he shows me how to chip the old mortar from the bricks, tells me the names of the tools. He puts the trowel in my hand and watches me tap the bricks in place. I watch him heat sheet copper with a blowlamp, he shows me how to tell when it is ready. His spit bounces off the metal with a zing.

A boy goes to sleep but before he can do so, he must think of those he loves, all his friends, his family, each of his pets – he fixes them in his mind and bids them goodnight. He wants to be good and he wants to be kind. He hopes to be clever and not do foolish things. What kind of man will he become?

Is it all dismantled? The house, that home, that childhood? The bricks and mortar still exist, but what occupies that now? What wasn’t done, must be accepted, it was simply not done – no more worth in it now, than it will ever have in the future. We must break bread with those we love, those that are still among us. We must cherish the things that still remain.

We whisper a mantra, all is well. And it is, whether we see it or not.

Bruce Springsteen plays as the rain thunders down on a silver Ford Granada. My father smokes a cigarette through the gap in the window, his sleeve glistening with rain. I’m just a boy. We are together, a family. The wolf is at the door but it is not yet in the house. Beyond the glass, the world crawls with water. Everything is alive and dancing.

A flower is no less beautiful in a world where I don’t exist.